Originally published in cfr.org on 18 June 2020

An ambulance driver, Mohammad Aamir Khan, changes his personal protective equipment at a crematorium in New Delhi. Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

COVID-19 cases continue to rise rapidly in South Asia. For months, South Asia was spared the worst of the pandemic.

Erik Fliegauf is a research associate and Priyanka Sethy is an intern for India, Pakistan, and South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations.

COVID-19 cases continue to rise rapidly in South Asia. For months, South Asia was spared the worst of the pandemic. Now, health-care systems in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan are struggling to treat hundreds of thousands of ill patients. Yet most countries are firmly on the path to reopening their economies.

India’s caseload rises to world’s fourth-largest: In early June, the government lifted its lockdown after two months of restrictions. Since then, India has seen a huge spike. At over 366,000 cases as of June 18, India has roughly 27 cases per 100,000 people. By comparison, the United States is dealing with around 650 cases per 100,000 people.

Indian states are mounting separate and largely uncoordinated measures to combat the rising tide of COVID-19 cases across the country. In Tamil Nadu, the southern state with the second-highest number of cases (over 50,000), authorities in Chennai are set to reinstate a strict lockdown on June 19. On the other hand, Delhi, which has the third-highest number of cases (over 47,000), remains open. Delhi’s neighbor Uttar Pradesh is fighting in the Supreme Court to keep its border with Delhi sealed, while Haryana is allowing movement to and from the capital.

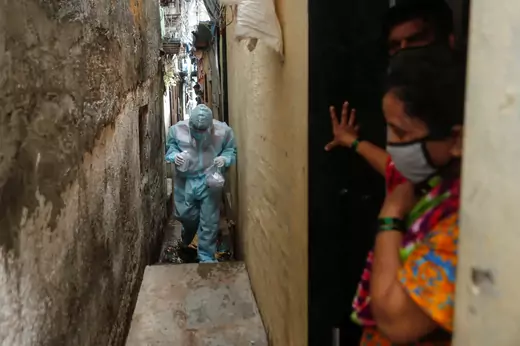

Maharashtra, the worst-affected state with 116,000 cases, saw the COVID-19 response in Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum, emerge as a surprisingly successful model. Accepting that social distancing was impossible in the slum, where as many as eighty residents share one toilet, authorities rolled out aggressive testing and screening measures. As a result, the rate of daily infections in Dharavi has been reduced to a third since early May.

Some major cities are facing severe administrative crises associated with the COVID-19 response. In Delhi, doctors of two municipal hospitals are threatening to resign due to non-payment of salaries. In Mumbai, the police force is spread thin with multiple departments being quarantined.

In response, the government has rolled out a “testing, tracing, and quarantining” strategy rather than reinstate an economically disruptive lockdown. The central government is imposing restrictions on movement in hot spot areas in twenty cities. Pakistan, like the rest of South Asia, is forced to make a difficult trade-off between letting the virus spread and letting its most vulnerable citizens struggle to survive without incomes.

Prime Minister Imran Khan has ruled out a sweeping lockdown in Punjab, despite the provincial government’s recommendations for tighter restrictions. Instead, the Punjab government imposed a two-week lockdown in certain areas of Lahore, the worst-affected city in Pakistan.

As cases rise, hospitals are operating beyond capacity and doctors are overworked. Adding to the list of public figures who have tested positive for the virus are Shehla Raza, a provincial minister in Sindh, and two former prime ministers, Yousuf Raza Gilani and Shahid Khaqan Abbasi.

“Confusion Reigns Supreme” in Bangladesh, declared the newspaper the Daily Star on June 16. Following the lifting of the nationwide lockdown at the end of May, Bangladeshis now await information about the timing and geographical extent of a new area-by-area lockdown system. In hard-hit “red zones” including much of Dhaka and Chittagong, people will not be allowed to enter or exit zones, leave their houses, or go to work. However, the nationwide roll-out of the system, which could ultimately place a quarter of the country’s area into red zones, has been delayed by a lack of granular data on where cases are located.

On June 16, over 4,000 cases were identified, a new daily high for a country with over 100,000 cases overall and 1,300 deaths. Like Pakistan, Bangladesh has a persistently high test positivity rate of 20%. A senior health official told the Dhaka Tribune, “It will be hard to assume when the peak day will come.” A report published by Transparency International Bangladesh uncovered many deficiencies in the country’s COVID-19 response. For example, only one lab in the entire country was authorized to test for the virus until March 25. Over the past two weeks, the daily testing rate has been just over half of laboratories’ capacity (24,000 tests per day) due to staffing shortages.

Afghanistan’s health care system flounders: The number of coronavirus cases in Afghanistan exceeds 27,000. COVID-19 adds more pressure to the country’s public health-care system, which is already overwhelmed by victims of conflict and malnourishment. Afghanistan is the poorest country in South Asia, with a GDP per capita that is around half of Nepal’s and one-third that of its neighbor, Pakistan. Meanwhile, the Taliban is ramping up attacks , targeting an already vulnerable health-care system and putting the health of millions at risk.

Acknowledging that public hospitals are operating beyond capacity, the government authorized private hospitals to perform COVID-19 tests for the first time on June 14, a move that was criticized by Kabul residents as they come with a price tag of around $100 per test, making them unaffordable for most Afghans. Additionally, the ability of private hospitals to conduct the tests has been called into question. Citizens have also claimed that certain hospitals in Kabul are running out of oxygen, an allegation that the hospitals have rejected. Desperate citizens are reaching out to dubious natural remedies as the health-care system fails them.

As Afghanistan struggles to cope, the EU has sent an aircraft with life-saving equipment, and also pledged an aid package of nearly $44 million to the country. However, the health organization Doctors Without Borders has had to withdraw from of a hospital in Kabul, following a tragic attack last month that killed 24 people and wounded 16.

Protests in Nepal: Nepal saw its largest single daily total of COVID-19 cases on June 18, bringing the total past 7,800. The number of deaths is relatively low, at just twenty-two. Under Nepal’s lockdown, imposed in late March, three of every five workers lost their jobs, and tourism receipts, singularly important to the economy, are predicted to drop by 60%. The government partially eased the lockdown in early June.

Nepal has seen ongoing peaceful protests against the government’s handling of the crisis. The protesters’ demands have focused on financial accountability and greater testing capacity [Pictures]. In response to these protests, the government announced that it would allow private hospitals to conduct COVID-19 tests. When a woman in a quarantine center accused three male volunteers of sexual assault, protestors took to the street to demand justice, and authorities temporarily shut down the center.

Caution in Sri Lanka pays off: The number of active cases in Sri Lanka peaked on June 4, and daily new cases are often in the single digits. Just eleven people have died out of 1,900 total cases, a fatality rate of just 0.6%. Over three-quarters of all cases are either navy sailors or arrivals from overseas. Sri Lanka, which has a relatively strong health-care system, successfully staved off a widespread outbreak by making testing widely available and investing early in a disease surveillance system. Still, Sri Lanka has been slow to relax restrictions and maintained a nightly curfew for months.

However, the Sri Lankan economy is in trouble. Saddled with debt for years and now facing low growth and declining revenue, Sri Lanka may be forced to accept yet another financial aid package from the IMF with stringent conditions, or else default. Nevertheless, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa criticized Sri Lanka’s central bank for not opening its coffers to revive the economy.

Bhutan faces budget shortfalls, but no fatalities: Over the last several months, Bhutan has proven to be a model for how small developing countries should contain the virus. Bhutan has had no fatalities and just 67 confirmed cases. National solidarity, public trust in officials, and even the public health background of the prime minister have helped. Like the rest of South Asia, however, Bhutan has struggled economically. While presenting the annual budget to the national assembly, Finance Minister Namgay Tshering announced that domestic revenue fell by 14% in the 2020–2021 fiscal year and predicted lower revenue next year due to a decline in tourism and trade-related taxes. Under its “Economic Contingency Plan,” the government will accept grants and loans, including bilateral loans, to stimulate the economy while reducing its deficit. One component is “Build Bhutan,” a labor ministry program which seeks to employ seven thousand job seekers in the construction sector.

The Maldives will allow tourism in July: The COVID-19 outbreak in the Maldives peaked on June 1, at 1,231 active cases, and has since fallen to around four hundred active cases. Eight people have died. The demographic profile of coronavirus patients in the Maldives is unique: around 60% of confirmed cases are men between the ages of 21 and 40, and over half are Bangladeshi citizens, mostly migrant workers. Low-skilled migrants from Bangladesh, nearly all of whom are men, constituted approximately 15% of the Maldives’ population in 2015. Most work in the construction sector and often face labor law violations, inferior living conditions, and obstacles to accessing health care.

The entire country entered the second phase of reopening by June 15, which means restrictions are lifted on movement outside of homes in the capital Male, as well as between non-affected islands. The tourism ministry released a statement that the country will begin welcoming international tourists again in July.

Leave A Comment